Two years ago when my first great nephew was born, my sister (his Grammy) told me about the rigamarole my niece and her husband went through to get their little bundle out of the hospital, including an inspection of the child safety seat. I laughed and drew her a verbal picture of what went down in our parents’ day. After forking over 150 bucks to the cashier (babies were cheaper by the pound then), my Dad slid into the driver’s seat of our seatbelt-less station wagon, my Mom took the passenger side (aka “The Death Seat”), cradling us in one arm like a potential human projectile while sporting a lit cigarette in her free hand. I imagine the words “I could really use a highball” were uttered more than once.

This came to mind when I ran across the latest Toyota ad in the current issue of “Vanity Fair.” Featuring a picture of a fresh-faced young mother holding her chubby toddler son, the headline reads, “Everyone deserves to be safe.”

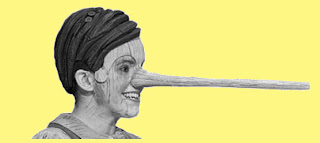

Putting aside the irony of the recall-riddled Toyota running such malarkey, it strikes me that “safe” is beginning to rank right up there with “green” as the feel good words of our age. But the more I looked at the ad, the more I realized it was the word “safe” coupled with “deserve” that, perversely, was causing my unease.

As the vignette about my first homecoming demonstrates, we used to do a lot of things that are now considered not only unsafe but illegal. From tearing around town on our Stingrays without bike helmets to hanging around the local saloon when our Dads felt the need for a beer, childhood’s past were, statistically, more fraught with pitfalls than today but, in my unscientific opinion, not nearly as much fun. In fact, it seems that the pendulum has swung so far to over-protection that immunologists are raising the alarm that children haven’t been exposed to enough of the run-of-the-mill germs that will build up their immune systems.

My musings about the high price we pay for being safe were brought into sharp relief by a non-fiction book entitled “War” that I finished reading a few days ago. Written by Sebastian Junger, author of “A Perfect Storm,” it chronicles the fifteen months he spent with a platoon stationed in a remote outpost in Afghanistan, the most combat-heavy spot in the whole country. If you’ve ever wondered why young American men would deliberately live in a God-forsaken shithole with no running water, no electricity, no cooked food and, worst of all, no women, while putting their asses directly in the line of fire, this book has the answers, and some you may not care to hear. This edited excerpt is one that really jumped out at me:

“War is a lot of things and it’s useless to pretend that exciting isn’t one of them. It’s insanely exciting. The machinery of war and the sound it makes and the urgency of its use and the consequences of almost everything about it are the most exciting things anyone engaged in war will ever know. War is supposed to feel bad because undeniably bad things happen in it, but for a nineteen-year-old at the working end of a .50 cal during a firefight that everyone comes out of okay, war is life multiplied by some number that no one has ever heard of. In some ways twenty minutes of combat is more life than you could scrape together in a lifetime of doing something else.”

And that includes being safe, whether it’s deserved or not.